By 7:12 a.m., I’ve already apologized to my kids three times for snapping.

Not because I’m angry. My brain is juggling too many unfinished loops. The clock ticking feels accusatory. My child is melting down over the first long sleeve shirt of the season (but it’s -5 out). I’m tired, my coffee is cold, and I’ve rewritten my to-do list three times since last night.

What my child sees is hesitation. What I’m doing is triage.

If I push, we may leave on time but everyone falls apart. If I wait, the morning is calmer but the structure collapses. There is no neutral option.

While calculating, my nervous system heats up. My voice tightens. His tone begins to match mine. I’m trying to play the competent adult who has it together and failing. By the time we get out the door, we’re depleted. My child is holding it together by force. I’m running on adrenaline and guilt, guilty that I pushed too hard or guilty that I didn’t.

The day hasn’t started. We’re already recovering. I’m questioning my sanity.

Welcome to a day in the life of a neurodivergent home.

Which begs the question: is my life chaos, or constant decision making under cognitive strain, with consequences at every turn?

I combed through research, scoured forums, and spoke with dozens of neurodivergent parents to bring you honest insights, practical strategies, and if all else fails, validation that you’re not in this alone.

Why Neurodivergent Parenting Is Unique

Neurodivergent parents and children share strengths, sensitivities, and struggles. We are expected to model calm and self regulation, even when we are lacking the tools to do so ourselves. Every day requires navigating our own triggers while supporting our children through theirs, making parenting a constant balancing act of empathy, restraint, and perseverance.

Neurodivergent parents of neurodivergent children often experience greater stress and cognitive overload than neurotypical parents of ND kids. That shared intensity hits hardest in the small, everyday tasks neurotypical parents often take for granted. Morning routines, meal prep, homework, or even play can feel like navigating a minefield of steps.

But shared neurodivergence is not only a source of strain. It also brings deep empathy, intuitive understanding, and an embodied awareness of what overload actually feels like. Parents align easily with their child’s internal state because they’ve lived it. They can laugh about shared quirks, name the chaos instead of hiding it, and find relief in not having to explain everything.

As one mother put it, “It’s just nice to be seen. Home time is free for all. We survive until structured environments return.”

This dual reality is what makes neurodivergent parenting different. There are moments of profound connection and moments where no one in the room is fully regulated. It is within this context that choices become harder and challenges, not failures, emerge.

Challenge 1: Executive Function Overload

“I have time to get things done, but I can’t remember what they are. I can’t keep a thought in my head for more than five seconds.”

Executive function is the invisible engine behind daily life: planning, sequencing, initiating tasks, holding information, and shifting attention. When both parent and child are neurodivergent, that engine is often running on fumes in the moments it’s needed most.

In a small poll I conducted with neurodivergent moms, executive function demands were identified as the most challenging part of parenting. These are not dramatic crises. They are ordinary moments that quietly stack up: getting dressed, packing lunches, transitioning out the door, remembering the steps of a game, or keeping track of what has already been done.

What makes this especially hard is the overlap. Many neurodivergent parents are trying to help their child build skills they themselves have spent a lifetime compensating for or are still actively struggling with.

As one parent shared, “If I get a card with the steps written out and go slowly, I can usually follow. But I still don’t know if I already did the previous step.”

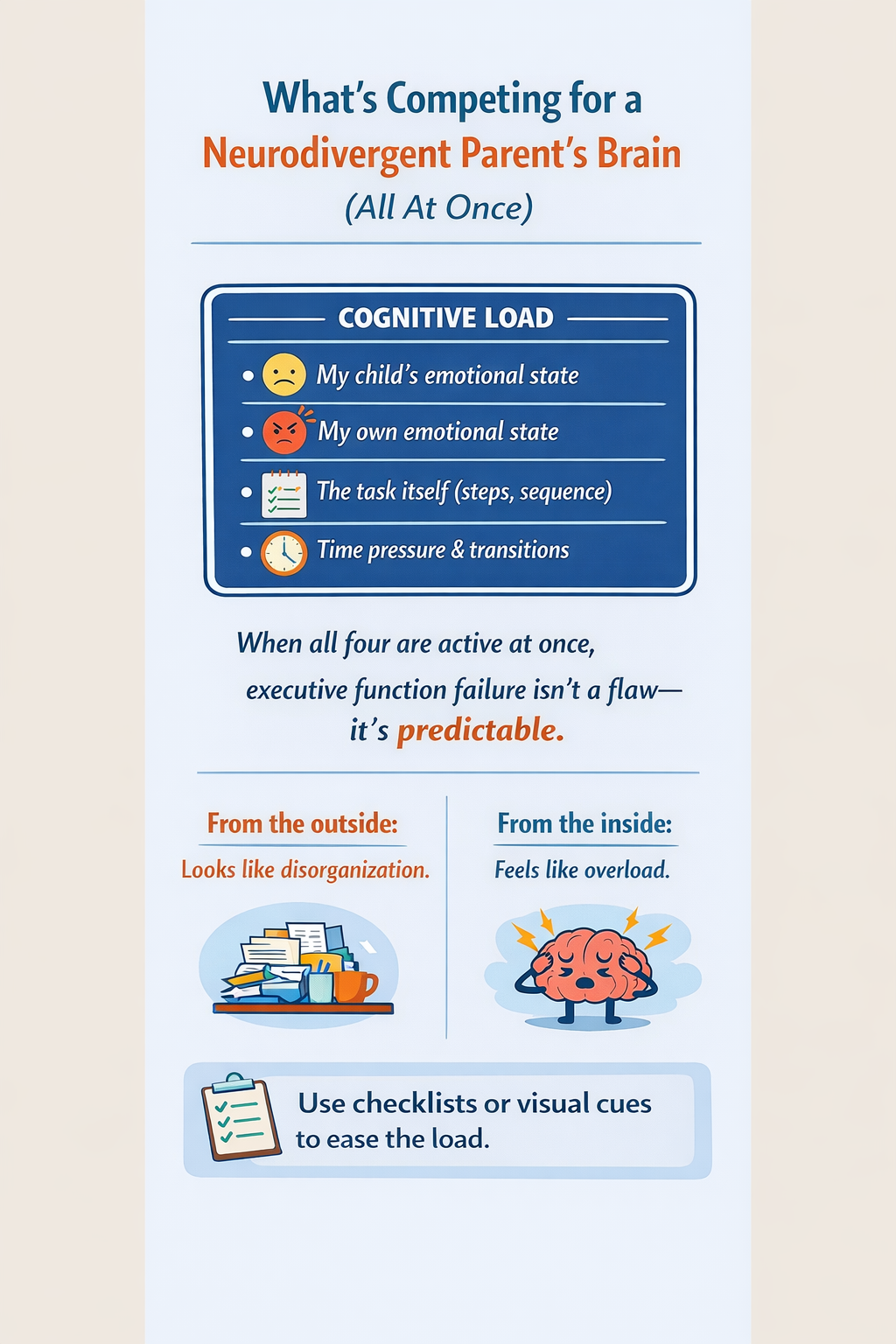

This creates a constant cognitive load. You are tracking your child’s regulation, your own regulation, the task itself, and the clock. There is little mental margin for error. When something goes wrong, it can look like disorganization from the outside. In reality, it is too many steps competing for limited working memory.

For neurodivergent parents, executive function overload is not a lack of effort. It is a mismatch between demands and capacity. When those demands repeat daily without a break, the cost compounds quickly- feeding directly into emotional exhaustion and burnout.

What helps (according to ND parents):

- Externalize tasks, even for things you think you should remember

- Checklists, timers, and visual reminders are not crutches, they are tools

- Checklists, timers, and visual reminders are not crutches, they are tools

- Reduce decision points

- Fewer choices mean less cognitive drain= same breakfast, shoes, and task order.

- Fewer choices mean less cognitive drain= same breakfast, shoes, and task order.

- One brain per task

- If you are helping your child regulate, pause other demands

- If you are helping your child regulate, pause other demands

- Aim for “good enough”

- Some days the goal is completion, not consistency

Challenge 2: Emotional Burnout and Co Regulation

“I’m so tired in my brain and my body. I love my kids, but some days I feel like I have nothing left to give.”

In my poll, emotional overload and burnout were identified as the second most challenging part of parenting. By the time many neurodivergent parents reach burnout, it is not dramatic. It shows up quietly- a shorter fuse, flattened affect, or the feeling of functioning on autopilot.

What makes this especially hard is the expectation of co-regulation. Children are said to borrow calm from adults, but many neurodivergent parents enter tough moments already depleted. Sleep deprived, overloaded, carrying decision fatigue or emotional residue from the day.

Several parents described staying externally composed while internally unraveling, knowing their child picks up on every shift in tone, posture, and energy.

“When both my kids need me at the same time and I’m already overwhelmed, I freeze. I know I’m supposed to stay calm for them, but my nervous system is already maxed out.”

Burnout does not mean you love your child less. It means you are being asked to provide more than your system can supply. This is not failure, it’s collapse.

What helps (according to ND parents):

- Protect recovery time

- Create intentional decompression through quiet moments, parallel play, or sensory breaks

- Create intentional decompression through quiet moments, parallel play, or sensory breaks

- Lower exposure, not expectations

- Reduce input by limiting transitions, noise, and competing demands

- Reduce input by limiting transitions, noise, and competing demands

- Tag team regulation when possible.

- Hand off regulation to an ‘on call’ partner, trusted friend or relative when you cannot be the calm one

- Hand off regulation to an ‘on call’ partner, trusted friend or relative when you cannot be the calm one

- Name internal limits out loud

- Saying “my brain is overloaded” reduces shame and escalation

- Saying “my brain is overloaded” reduces shame and escalation

The biggest help for parents is not learning to stay calmer, but reducing how often they are pushed past capacity. When burnout is already present, co-regulation cannot be forced.

Challenge 3: Feeling Judged

“I wish I knew how other parents see me. I feel like I’m always doing something wrong.”

The third most persistent challenge was feeling judged by other parents, teachers, or professionals. This judgment is rarely explicit. It shows up in raised eyebrows at school pickup, unsolicited advice, or assumptions like “have you tried being firmer?”

For neurodivergent parents, this scrutiny carries extra weight. Many are already masking, monitoring tone, facial expression, and behavior in public. When parenting challenges appear, they are often interpreted as a lack of effort rather than a reflection of limited capacity.

One father shared, “How am I supposed to teach my kids how to socialize when I don’t even know what that looks like?”

Several parents described the same loop: questioning instincts, over explaining decisions, or pushing beyond limits to avoid appearing incompetent. This pressure backfires, increasing shutdowns and emotional spillover later.

“I can handle my kids. What I can’t handle is feeling watched while I do it.”

Judgment does not only hurt emotionally. It increases cognitive load. It shifts attention away from the child and onto performance. Over time, even thoughtful, informed parents begin to doubt themselves.

You are not doing anything wrong. Being evaluated by a system that does not account for your lived reality comes with too high a price.

What helps (according to ND parents):

- Choose when to engage or disengage.

- minimize unhelpful conversations or leave situations where scrutiny outweighs support.

- minimize unhelpful conversations or leave situations where scrutiny outweighs support.

- Practice selective disclosure

- Stop overexplaining yourself or your child. You do not owe everyone your diagnosis, reasoning, or full story.

- Stop overexplaining yourself or your child. You do not owe everyone your diagnosis, reasoning, or full story.

- Anchor decisions internally

- Ask one simple question- “Is this helping my child feel safer or calmer?”

- Ask one simple question- “Is this helping my child feel safer or calmer?”

- Seek ND affirming spaces where masking is not required

- Feeling seen reduces the need to defend or justify choices elsewhere..

Judgment may still show up. It does not have to live rent free. Giving it less power lowers self doubt and conserves energy for what matters most: you and your child.

A Word About Self Care

Research suggests that activities providing structure, predictability, and sensory regulation are often more restorative for neurodivergent adults than passive rest.

Parents described feeling calmer when engaged in hands-on, purposeful activities that quiet mental noise and restore a sense of agency. Cooking, gardening, puzzles, or DIY projects- often the same activities their ND children gravitate toward, can provide a meaningful reset.

“Art feels grounding because there’s no right way to do it. When I’m drawing or painting, my brain finally slows down. I’m not managing anyone else, not making decisions, I’m just there.”

Find those small pleasures that bring your nervous system back ‘online.’

Redefining Norms

Shared neurodivergence is a double edged sword. It brings empathy, intuitive understanding, and lived insight. It also brings triggers that mirror each other, parallel meltdowns, and moments when no one in the room is fully regulated. Parenting here requires recalibration, not control.

Many parents described relief when they stopped chasing the myth of the perfect parent. Not by giving up, but by redefining success. Safety over appearances. Regulation over compliance. Values over what ‘looks best’ on the outside.

If this feels familiar, it is not because you are doing it wrong. You are carrying a double load.

Parenting in neurodivergent homes is not about mastery. It’s about recovery, repair, and return, again and again. Naming the struggle does not weaken you. It clarifies what you are managing.

You do not need to fix yourself. You do not need to parent like anyone else. And you do not need to do this alone.

At Shining Steps, we work with neurodivergent children and their families through an affirming, whole child lens. If this article resonated, check out our blog for similar content or contact us today for guidance that understands your child and you.

References

- Leadbitter, K. (2024). Parents of neurodivergent kids need support—but those who need it most often wait longer.

- Crane, L., et al. (2024). Parental experiences and stress in families of neurodivergent children.

- Research in Developmental Disabilities (2024). Executive function demands and parental stress in families of neurodivergent children.

- Autism in Adulthood. (2025). Neurodivergent parenting and systemic barriers to support.

- Hooper, J. (2023). Why being a neurodivergent parent is tough.

- Absurd and Wondrous. (2024) We need to talk about neurodivergent parents.